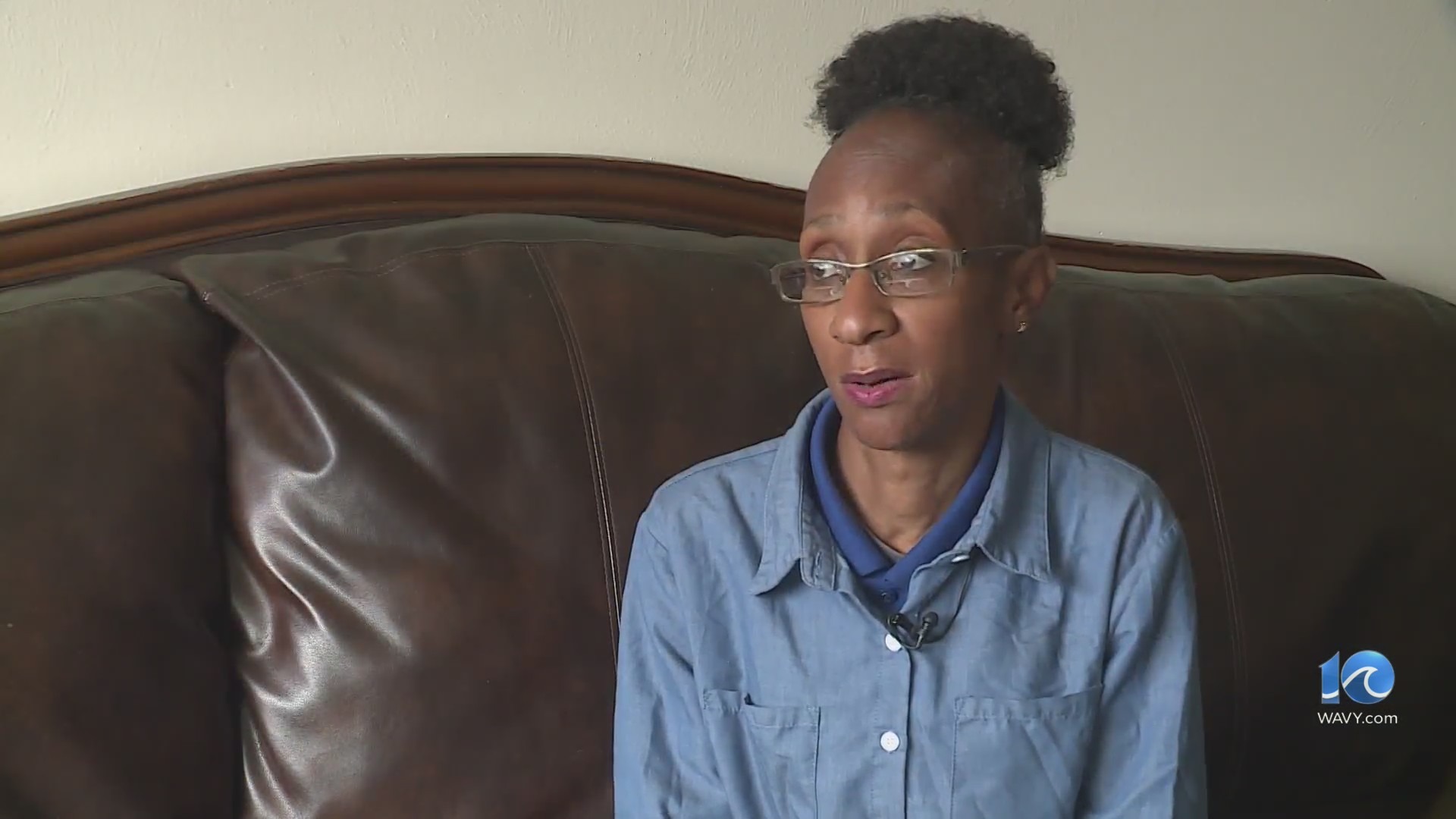

HENRICO COUNTY, Va. (WRIC) — This Veterans Day, 8News is amplifying the voices of veterans from all walks of life. Stephanie Merlo, a gay solider who served while “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was in place, shared how that policy still haunts her decades later.

As she would have been penalized for living her authentic life because of this law, Merlo went to great lengths to hide her true self — but it came at a cost that she’s still paying today.

“‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ is no longer a thing, but it’s still a thing,” Merlo said.

Merlo decided to sign up for military service while in high school in Chesterfield County. The 9/11 tragedy was the catalyst.

“We want to give back, we want to serve our country, we want to help us grow, we want to help protect our people,” Merlo said. “And I remember how the room felt when [9/11] happened and everybody was looking at each other confused, like, ‘What does that even mean?'”

For Merlo, it ultimately meant enlisting in the army in 2003 — during a time when the U.S. Military was observing “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” which was instituted under the Clinton administration in 1994.

“If you are gay, it’s basically ‘Don’t say anything about it — as long as the military doesn’t find out about it, you’re okay,'” Merlo said of what that law was in practice. “So you weren’t allowed to openly be yourself. They felt that it would bring down the morale of the units, [that] it would distract from the mission at hand.”

Merlo said she tried to keep her secret hidden — even dating men where she was stationed in Germany to mask it.

“The single hardest part was keeping a lie,” Merlo said.

As those relationships stalled, suspicion grew — and so did the harassment.

“And it was intense,” Merlo said of that harassment. “I had soldiers banging on my door, asking me to let them in after I had a drink or two.”

What traumatized her the most, however, was a sexual assault that came at the hands of another female soldier.

“I remember so much confusion,” Merlo said when talking about the assault. “[I thought,] ‘What is happening? This does not feel right, this hurts.'”

Merlo felt she could not report the assault because of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

“I felt, if I had reported it, then they would say, ‘Well, what was your part in this? What did you do? Are you sure you didn’t ask for it?'” Merlo said. “But it was my career on the line, and [I’d] just got there. And I felt like I couldn’t say anything.”

But carrying that pain with her wasn’t easy.

“It was so much turmoil in my brain and I fell into a deep deep depression,” Merlo said.

This depression was something she dealt with for the remainder of her military service, which ended in 2007 when a physical injury led to her discharge.

“Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was repealed in 2011 — but it was too late for Merlo to personally benefit from it.

Today, Merlo shares a home in Henrico County with her wife of 5 years and their “fur babies.” However, she continues to deal with PTSD, anxiety and depression, all stemming from her service.

“What really sucked is [that] I had no one I could talk to about it because of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” Merlo said. “If I was allowed to say something, or if I was allowed to report it, where would my life be right now? Would I not suffer from PTSD and other forms of trauma, had I been able to kind of get that type of help and justice at the time?”

Though “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” ended in 2011, Merlo insists the culture doesn’t change quickly. She said that, while other veterans just like her still deal with the effects of the now-defunct policy, she believes current LGBTQ+ military members continue to endure harassment and discrimination — even if it’s more subtle.

Just recently, hundreds of veterans who received less than honorable discharges under “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” have had their statuses changed to honorable, allowing them to now enjoy full veterans’ benefits.