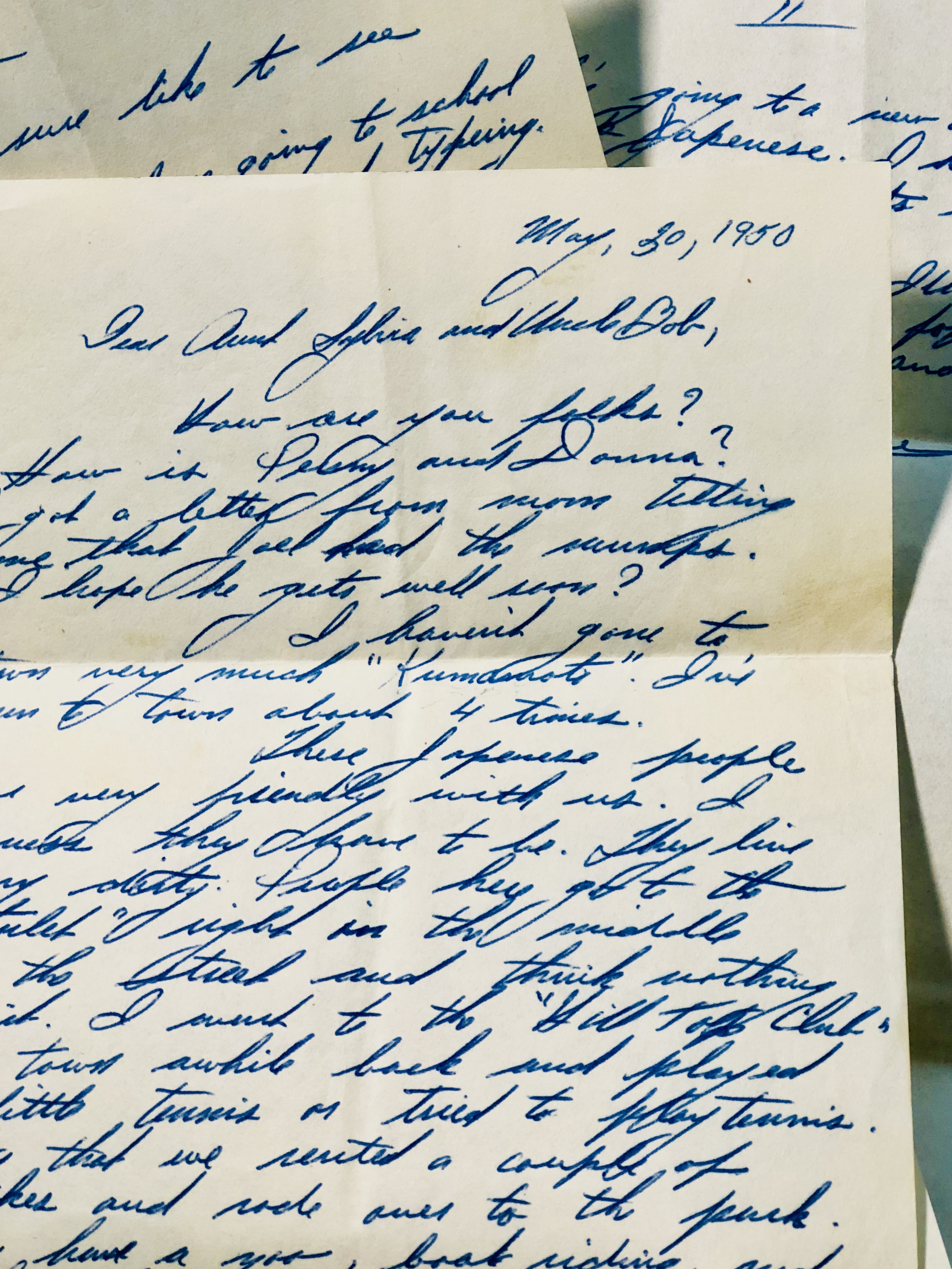

HAMPTON, Va. (WAVY) – Nearly 70 years later, Lana Dorsey still remembers getting letters from her older brother, Ronnie.

“I bought a beautiful camera today for $53 and it’s really a beauty,” he wrote in one letter, dated May 30, 1950. “I’m going to a new class next week to take up Japanese.”

Lana and her family never got to see those pictures, or find out how the Japanese lessons went, because that’s likely the last letter Private First Class Ronald Raboye ever wrote.

“A telegram came that he was missing in action on my mother’s birthday, which was July 11 [1950],” Lana said. “My mother had a nervous breakdown, and my other brother Joel and I were sent to an aunt in New York for about three months until she could get herself together.”

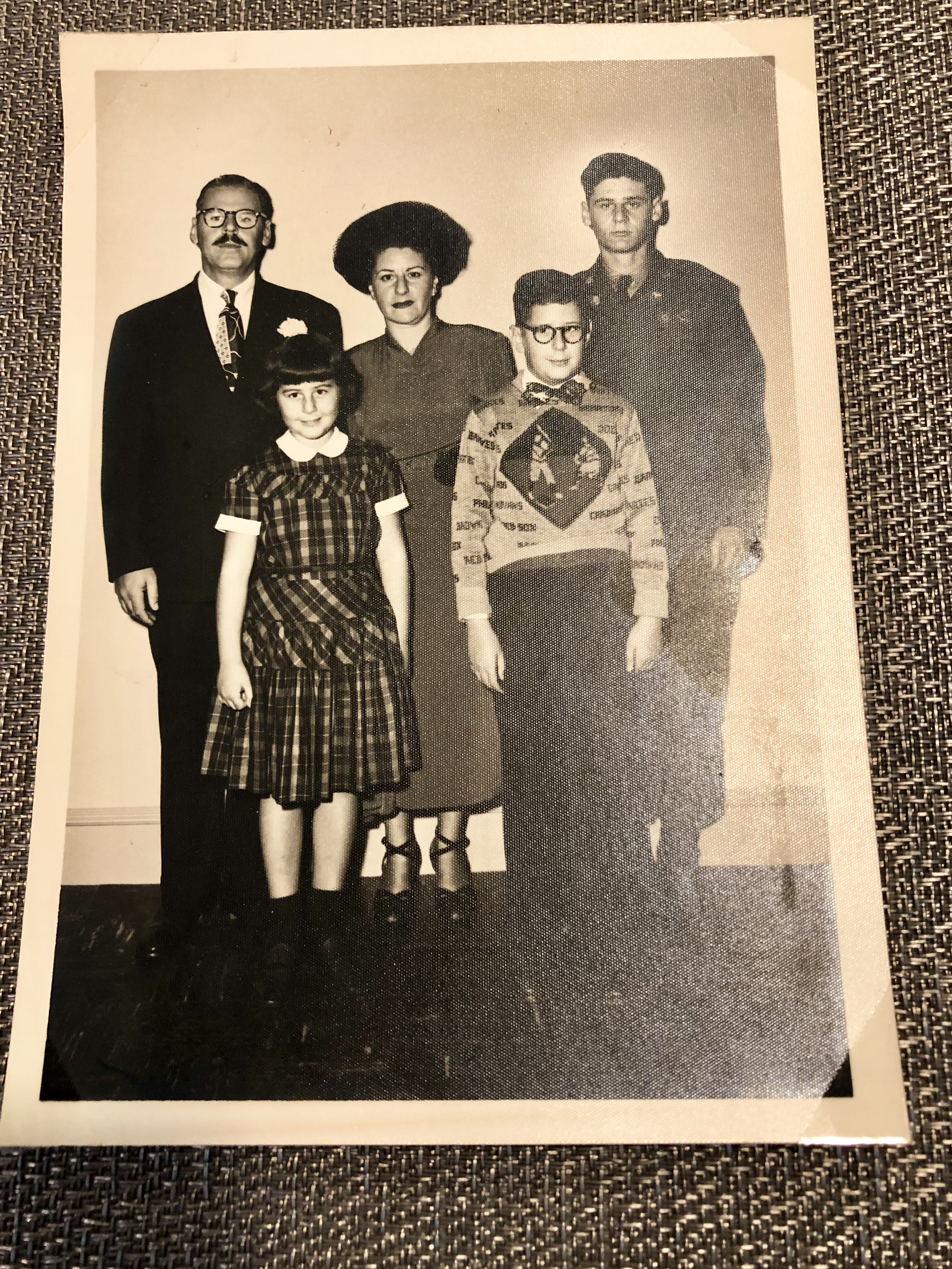

Up until the day the telegram came, Lana remembers her family life as the post-war American ideal: two older brothers, and happily married parents, Jack and Anne Raboye.

“[My mother] was a very outgoing, talented artist, a marvelous opera singer,” Lana said. “My father, he didn’t worship the ground she walked on, he worshipped the water she walked on.”

The family moved around the East Coast for Jack Raboye’s work, but Lana’s clearest memories of her brother are from a farm in Hampton.

“There was always something going on,” she said. “I remember he taught me how to shoot a gun, he taught me how to play baseball.”

Ronnie was 11 years older than Lana, but she still remembers his decision to enlist during peacetime, when he was just shy of 18 years old.

“It would be an opportunity for him to travel, which he hadn’t done before and he thought it was a good time,” Lana said. “Well, unfortunately, it ended up not being such a good time.

But Ronnie still didn’t know that, and neither did the his family. First, there was the excitement of joining up, and heading off to Tennessee, Texas, California and Japan.

Within months, Ronnie’s story changed from a new adventure to a grim, deadly reality.

“Boom, all of the sudden, they were the first round, the first group to go to South Korea,” Lana said.

At the time, the Raboyes didn’t even know Ronnie had left California, much less that he had been sent into war.

They found out only when the telegram came, saying Ronnie was missing in action. About a month later – the family got more devastating news.

“They received another letter from Washington saying he has been captured, he’s a POW,” Lana said.

Lana knows a lot now about her brother’s brief time in Korea. The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency issued a report earlier this year, detailing his regiment’s moves and what happened after they were captured.

Back then, however, the Raboyes had no answers, only fear and grief.

“We didn’t hear anything for five years, until 1955, and that’s when we actually got the ‘He’s dead, he died January 1, 1951.’”

That information came from Army Private First Class Johnny Johnson, who risked his life in the camp to secretly record the names of 496 fellow prisoners who died.

“My parents didn’t believe it. They said ‘impossible.’”

In the five years between Ronnie’s imprisonment and confirmation he was dead, Lana’s parents had been writing letters and making contacts in Washington to get answers.

That never stopped.

“[My mother] never believed he died,” Lana said. “I think my father followed her, but I think in his heart of hearts, he knew Ronnie was gone. But just to pacify her, he would continue to write these letters, up until the 90s.”

Lana did believe the report, and she accepted her brother was gone.

“As I got older and had my own child, I could fully understand how she had a nervous breakdown, how she held onto the hope for all those years.”

That disbelief and hope was especially necessary, because according to Johnson’s report, Ronnie didn’t die a quick or peaceful death. He was in captivity for about six months before he died in the cold Korean winter.

“Every once in awhile, I’ll have a flashback and think how terrible it must have been to die of starvation,” Lana said. “I try very hard to keep that on the side and not let that creep into my mind.”

These days, Lana does have some hope for that final piece of closure: that her brother’s remains may come home.

“I’m so glad we’ve opened the door again,” she said, referring to North Korea’s repatriation of 55 boxes containing human remains earlier this year.

Lana has a decent idea of where her brother’s body would be, and it hasn’t been excavated yet.

But she’s done all she can to make the connection when that does happen.

“My DNA and my daughter’s DNA, as long as they’re in Washington, I put my faith in that because I’m getting older and I don’t know how much longer I’ll be around,” she said. “We know that no matter how long it takes, they’re never going to stop looking.”

Part one can be found at this link.