NEW HAVEN, Conn. (WTNH) — Celebrated African American folk artist Winfred Rembert, who survived a near-lynching as a teenager in the Jim Crow South, says he’s not optimistic about the future for black people in the United States.

“This skin turns people off,” said Rembert, who lives in New Haven, Connecticut. “I don’t know why. Out of all the skins in the world when it comes to black skin, people are turned off, and they’ll do things to black skin that they wouldn’t do to any other skin. Why is that? Why is it so easy to pull the trigger on a black man? Why is it so easy to tase a black man when he hasn’t done a damn thing? Why is it so easy to do that? Why is it so easy to slap his face and knock him to the ground and mistreat him just because his skin is black? Not just in the streets. I mean in corporate America. It’s the same thing.”

Rembert’s skin has been the justification for white men to beat him, attempt to lynch him and even force him to work in cotton fields. Rembert detailed those experiences in the films “All Me: The Life and Times of Winfred Rembert” and “Ashes to Ashes.”

WATCH: Winfred Rembert recounts his life experiences

The 74-year-old now carves his scars onto another skin: leather etchings that depict his memories and add up to the heritage of an entire country.

“I can’t see a better future when I look at George Floyd.”

Rembert’s depictions of police beatings and the nightmares that stalk young black men are not historical depictions.

“I can’t see a better future when I look at George Floyd,” he said. “I can’t see a better future when I look at my son.”

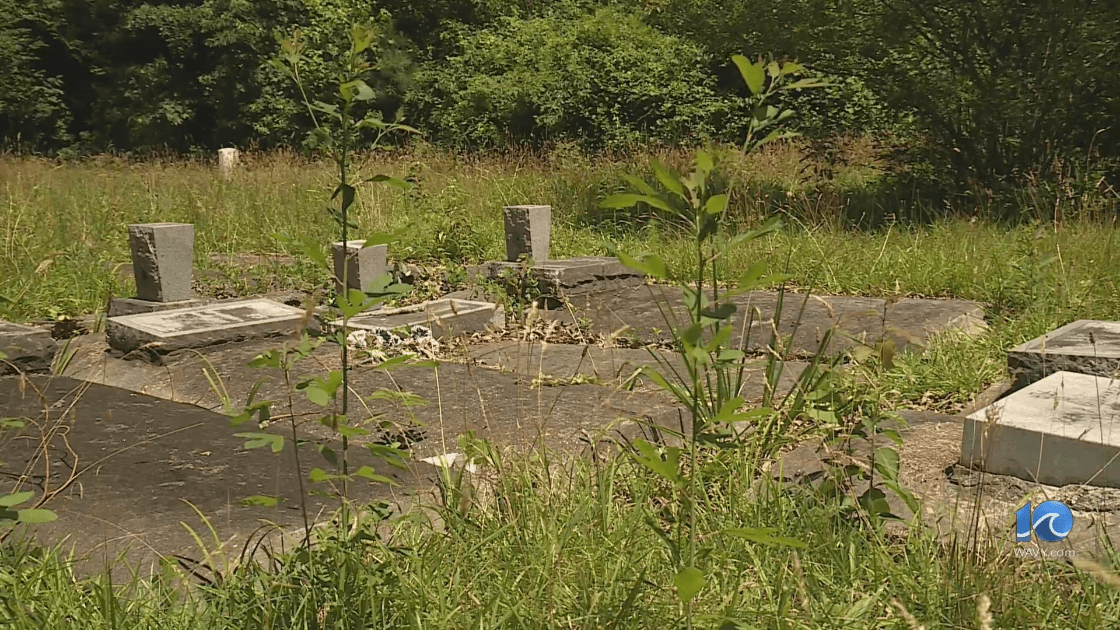

His skin, Rembert said, is “chasing me to my grave. Chasing my son right behind me.”

On this Juneteenth, which many hope will mark the dawn of a new freedom, a true freedom — from systemic racism, violence and economic oppression — Rembert won’t play to platitudes.

“I would love to sit here with you and say, ‘we’re going to celebrate and we’re going to have a good time,’ but I have no hope. To me right now, Juneteenth is just a word.”

But Rembert’s son John disagrees. He shares his father’s skin, in a world that has given him plenty of his own scars.

John said he is ready to share his father’s burden, too.

“To survive captivity in Africa, Middle Passage, slavery, wars, civil rights, gang violence and then to still be here … there’s hope,” John said. “There’s hope. If we’re going to be eradicated, it would have happened a long time ago. We refuse to go anywhere. We want our place in this world as Black Americans. We want our identity.”

He wants a world where he doesn’t have to worry about whether the way he talks, walks, dresses, laughs or shows anger will mean the loss of his life or livelihood.

WATCH: John speaks about his challenges, changes he hopes to see

A world where scars can heal.

“We have to do something different now. We have to start creating a new history.”