NORFOLK, Va. (WAVY) — A federal lawsuit has been filed on behalf of two area residents who are challenging the legality of Flock cameras in the city of Norfolk.

Flock cameras, a brand of automatic license plate readers, are in all seven cities in Hampton Roads as well as the municipalities of the historic triangle.

They’ve been installed in the name of fighting crime.

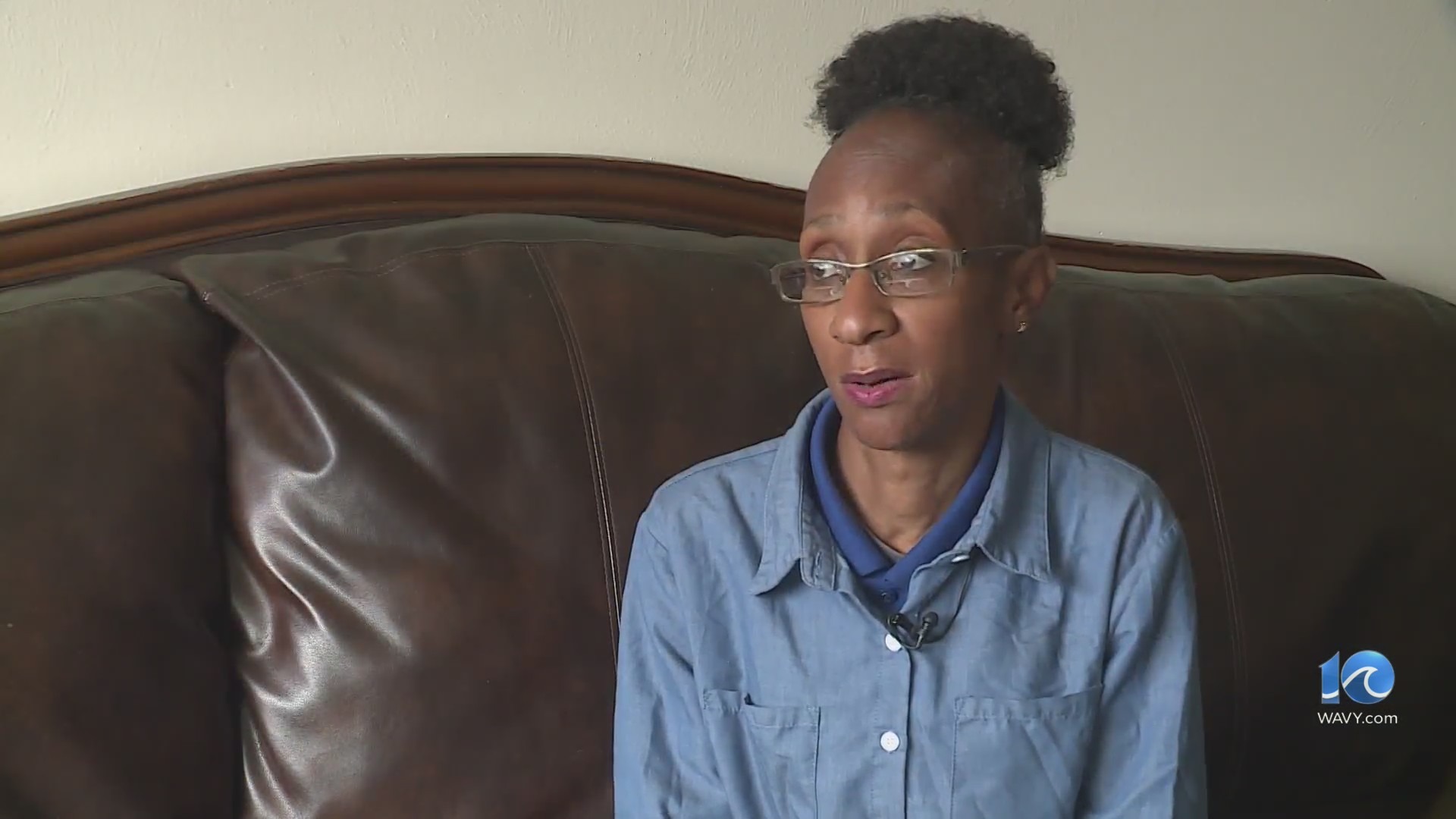

However, the lawsuit filed Monday by the Institute for Justice on behalf of Norfolk resident Lee Schmidt and Portsmouth resident Crystal Arrington, alleges they are fighting to protect constitutional rights.

“I don’t like the government following my every movement and treating me like a criminal suspect,” Schmidt said, “when they have no reason to believe I’ve done anything wrong.”

Arrington said her work requires her to drive around Norfolk often, “and it’s incredibly disturbing to know the city can track my every move during that time.”

In 2023, Norfolk Police installed 172 Flock cameras across the city. Police Chief Mark Talbot says their use has “substantially” lowered crime in the city.

“The technology is ultimately a tool we’re able to use to leverage good policing into good outcome,” Talbot said back in January. “The Flock system no doubt has gone a long way toward helping us reduce property crimes, in particular, stolen vehicles, I’m sure it’s helped us reduce other property crime, like theft from vehicles, and it’s helped us solve violent crimes.”

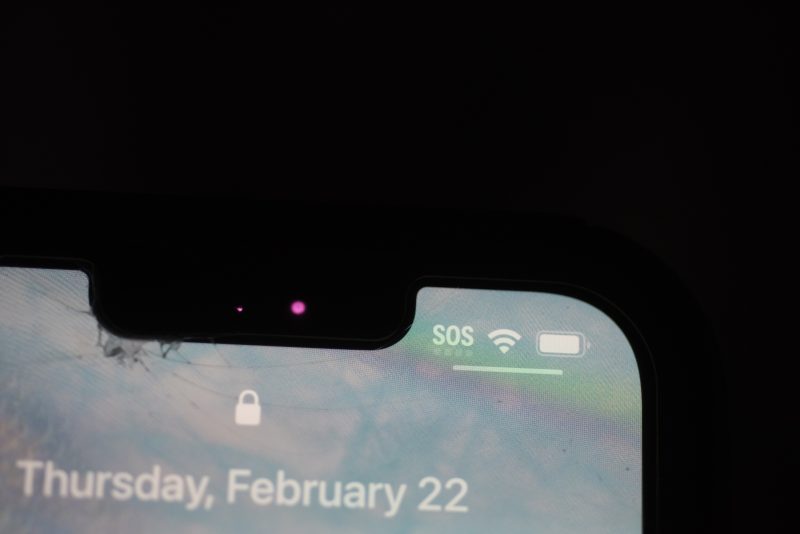

The cameras, which take a photo of every license plate that passes through and saves it in a database for 30 days, can scan across several lanes of traffic and capture tag information 24/7.

“Norfolk has created a dragnet that allows the government to monitor everyone’s day-to-day movements without a warrant or probable cause,” said Institute for Justice attorney Michael Soyfer.

The institute says that because Flock pools its data in a centralized database, police across the country have access to the information — more than 1 billion monthly datapoints.

“Following someone’s every move can tell you some incredibly intimate details about them, such as where they work, who they associate with, whether or not they’re religious, what hobbies they have, and any medical conditions they may have,” said IJ senior attorney Robert Frommer. “This type of intrusive, ongoing monitoring of someone’s life is not just creepy, it’s unconstitutional.”

A ruling in Norfolk Circuit Court in a case against Jayvon Antonio Bell noted that “the citizens of Norfolk may be concerned to learn the extent to which the Norfolk Police Department is tracking and maintaining a database of their every movement for 30 days. The Defendant argues ‘what we have is a dragnet over the entire city’ retained for a month, and the court agrees.”

Bell was one of two people who pleaded guilty in September to an armed robbery of a video game store in Norfolk.

In a news release announcing the filing of the lawsuit, the Institute for Justice cited that Flock systems similar to Norfolk’s “have been repeatedly abused.” It also said the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that “the use of modern technologies for prolonged monitoring of someone’s every movement is a ‘search’ under the Fourth Amendment and thus requires a warrant.”

It said the case is part of its Project on the Fourth Amendment, which it said “seeks to protect the right of Americans to be secure in their persons and property.”

A news conference regarding the lawsuit took place at 11 a.m. at the Walter E. Hoffman Courthouse, which can be viewed in full below:

“While the City of Norfolk cannot comment on pending litigation, the City’s intent in implementing the use of Flock cameras (which are automatic license plate readers) is to enhance citizen safety while also protecting citizen privacy,” Kelly Straub, a spokesperson for Norfolk, said.

In a statement from Flock Safety, it stated that license plate readers “do not constitute a warrantless search because they take photos of cars in public and cannot continuously track the movements of any individual.”

Read Flock Safety’s full statement below:

“Fourth Amendment case law overwhelmingly shows that license plate readers do not constitute a warrantless search because they take photos of cars in public and cannot continuously track the movements of any individual. Appellate and federal district courts in at least fourteen states have upheld the use of evidence from license plate readers as Constitutional without requiring a warrant, as well as the 9th and 11th circuits. Since the Bell case, 4 judges in Virginia have ruled the opposite way — that ALPR evidence is admissible in court without a warrant.

“License plates are issued by the government for the express purpose of identifying vehicles in public places for safety reasons. Courts have consistently found that there is no reasonable expectation of privacy in a license plate on a vehicle on a public road, and photographing one is not a Fourth Amendment search.”