MANTEO, N.C. (WAVY) — The statue of a man in Manteo diligently stands watch, immortalizing the unwavering will of humanity. Many pass by, though some are unaware of the tremendous acts of bravery and perseverance by the person this statue represents: Richard Etheridge.

“Black history — this is American history,” said Joan Collins, board member of the Pea Island Cookhouse Museum. “It should not be confined to just recognizing it on Black History Month. So I say that as loud as I can possibly say it and encourage everybody to think about that.”

Born into slavery shortly before the Civil War, Etheridge would find his way out, and eventually, into battle. He fought for the Union, including the Battle at New Market Heights. Etheridge also spent time advocating for civil rights on Roanoke Island.

After the war, Etheridge joined the Bodie Island Life Saving Station at the lowest rank. White and Black Americans worked side-by-side, something uncommon at the time, according to Collins.

“They were called checkerboard stations, or stations with checkerboard crews,” she said.

Etheridge was educated, able to read and write. He proved his worth as an agile surf man. In 1880, it was recommended he become the keeper at the Pea Island Life Saving Station.

“So he rises from the lowest in rank to the highest in rank,” Collins said. “The Blacks that are there remain and then Etheridge gets a couple of Blacks that were at other stations, and that’s in essence how the all-Black Pea Island crew is established.”

His team became the first all-Black life saving crew. This would lead to what they are perhaps best known for — the rescue of the E.S. Newman on Oct. 11, 1896. Coquetta Brooks, secretary of Pea Island Preservation Society Inc., often retells the story of this daring rescue.

“In a full blown hurricane,” Brooks said, “those waves were as high as a three-story building — the wind, so loud, that you couldn’t hear the person standing next to you.”

Blown 100 miles off course, the vessel with nine people is caught up in the storm and became shipwrecked. Captain S.A. Gardiner fires off a flare.

“He knew of the lifesaving station, and this was the only hope of being rescued,” Brooks said. “They took out the Lyle gun. It sank because of the muck and the mire and the water. They couldn’t use the boat, they couldn’t use the Lyle gun. Something had to be done.”

Etheridge and his team took a chance on something no other lifesaving crew had ever tried.

“They tied the ropes around themselves, they tied them to each other, they extended them back so that the other men could hold on,” Brooks said.

With ropes tied around their fellow crew members, the surf men swam out to the ship amid hurricane conditions. Even at this point in history, the Newman’s passengers did not care who rescued them.

“In life-or-death situations, race is not a factor,” Brooks said.

The wife of the captain gives the surf men their 3-year-old child first. Then, one by one, the rest are brought to shore.

“All nine lives were rescued,” Brooks said. “What started at 9 p.m. ended at 1 a.m. Captain Gardner went out there, everything was gone. His vessel was destroyed. This was supposed to be a regular run. I’m sure he thought about how he could have lost the lives of his family, his crew, and himself. The only thing that remained is the sign board, the E.S. Newman.”

During the lives of Etheridge and his team, they would hardly be recognized for this incredible feat of strength and bravery — not until 100 years later, when Etheridge was posthumously given the Gold Life-Saving Medal by the U.S. Coast Guard.

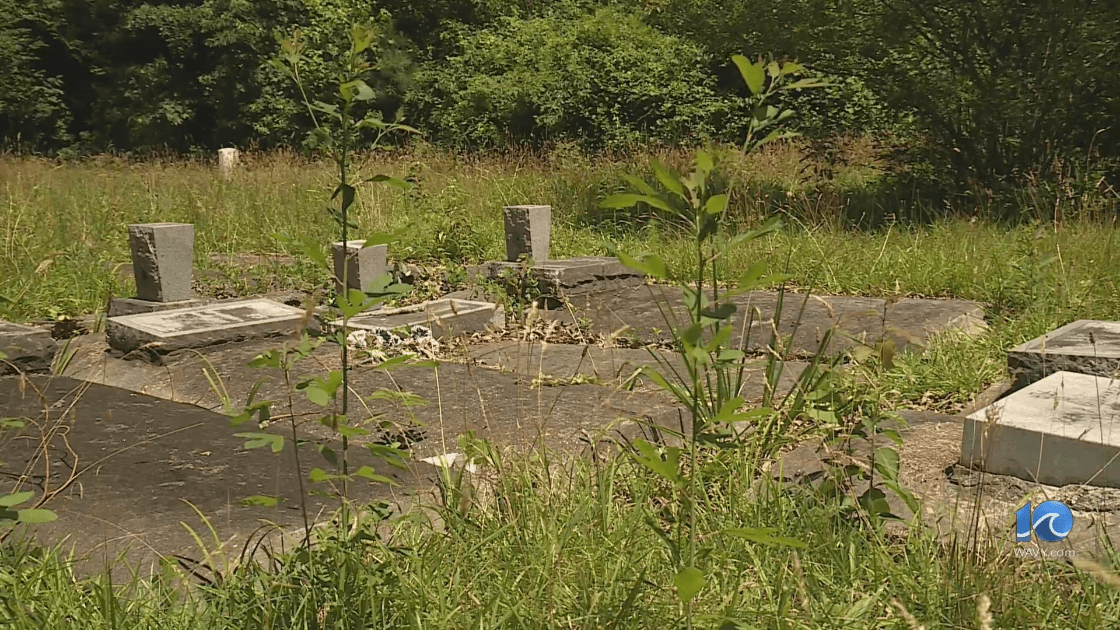

Descendants of the surf men now run and maintain the Pea Island Cookhouse museum, preserving things like payroll documents from that very lifesaving crew.

“Capture, keep, save moments because they get lost so easily,” Collins said.

They work to ensure the life of Richard Etheridge and all he accomplished is passed down to the next generation.

“I don’t think it’s talked about enough. I think it should be talked about more,” said Barkely Collins, a descendant of one of the surf men.

“I think it’s crazy about how Lebron James can be like the number one player, everybody knows Lebron James, but nobody knows who Richard Etheridge is,” said Jason Berry, another descendant of a surf man.

Joan Collins said the incredible rescue of the E.S. Newman does not alone define the legacy of this team. Through enduring slavery, the Civil War, fighting for rights and fighting to save countless lives at sea, Collins believes they are significant to American history.

All of the people interviewed for this story are descendants of the surf men.